Understanding worm behavior with machine learning

The big question I tackled for my graduate thesis is how does an animal process sensory information and make behavioral decisions. To study this using the round worm C. elegans, I first built an instrument that can probe many worms and record their behaviors. Then I used unsupervised machine learning to map out the behavioral repertoire of the animal using thousands of hours of recordings. Finally, I developed mathematical models that can predict the worm’s decision making for a given stimulus. These detailed methods and results are published in the journal eLife: Temporal processing and context dependency in Caenorhabditis elegans response to mechanosensation. The source code is also available.

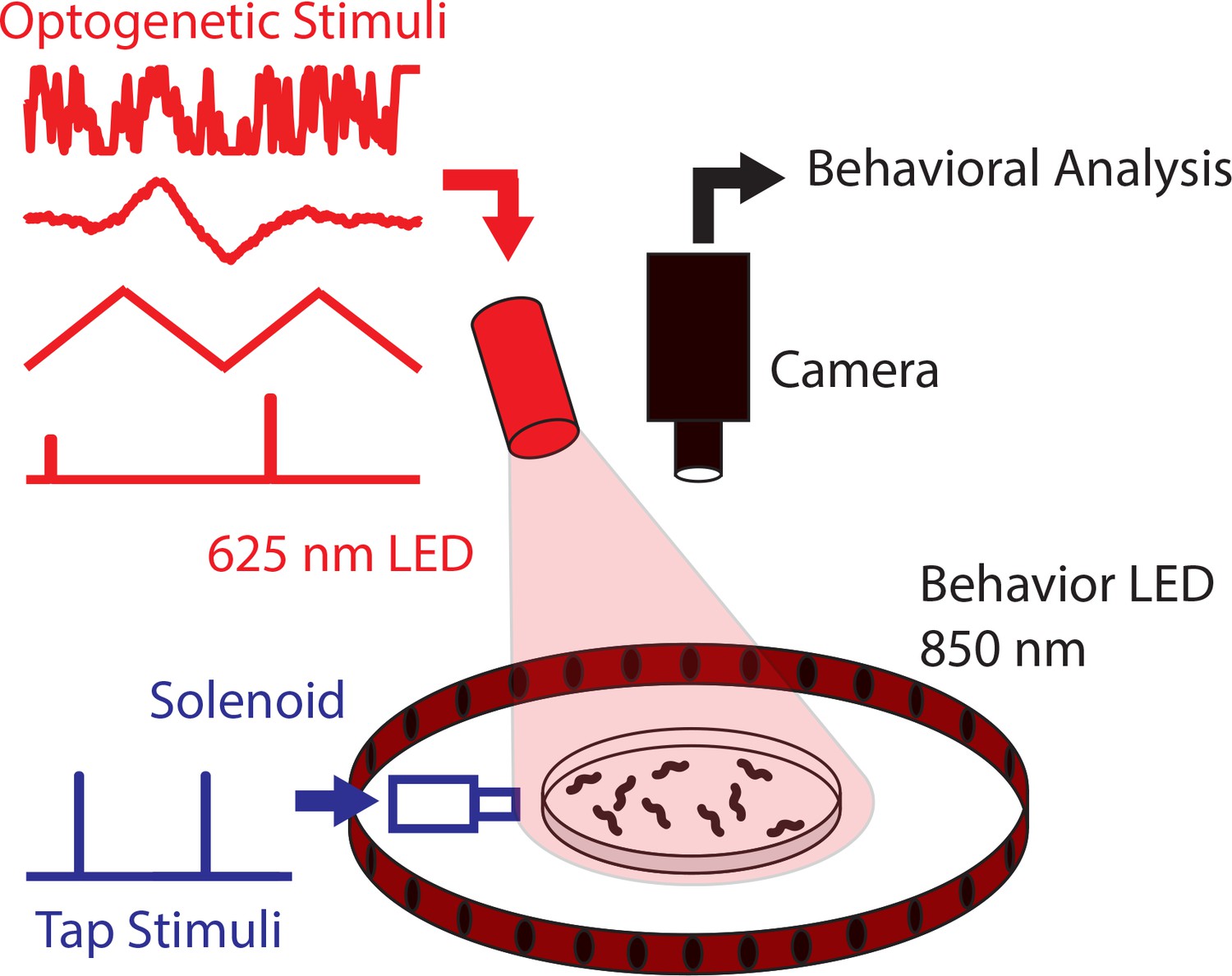

I first built instruments that can deliver physical and light stimulation to a plate of animals while recording their responses using a camera. This high-throughput assay allows me to collect hundreds of worm-hours of behavioral data in a single day, allowing me to conduct experiments that are simply not possible in single animal studies. This simple instrument is used to gather all the data used in the study, which encompasses over 8000 animal-hours of data.

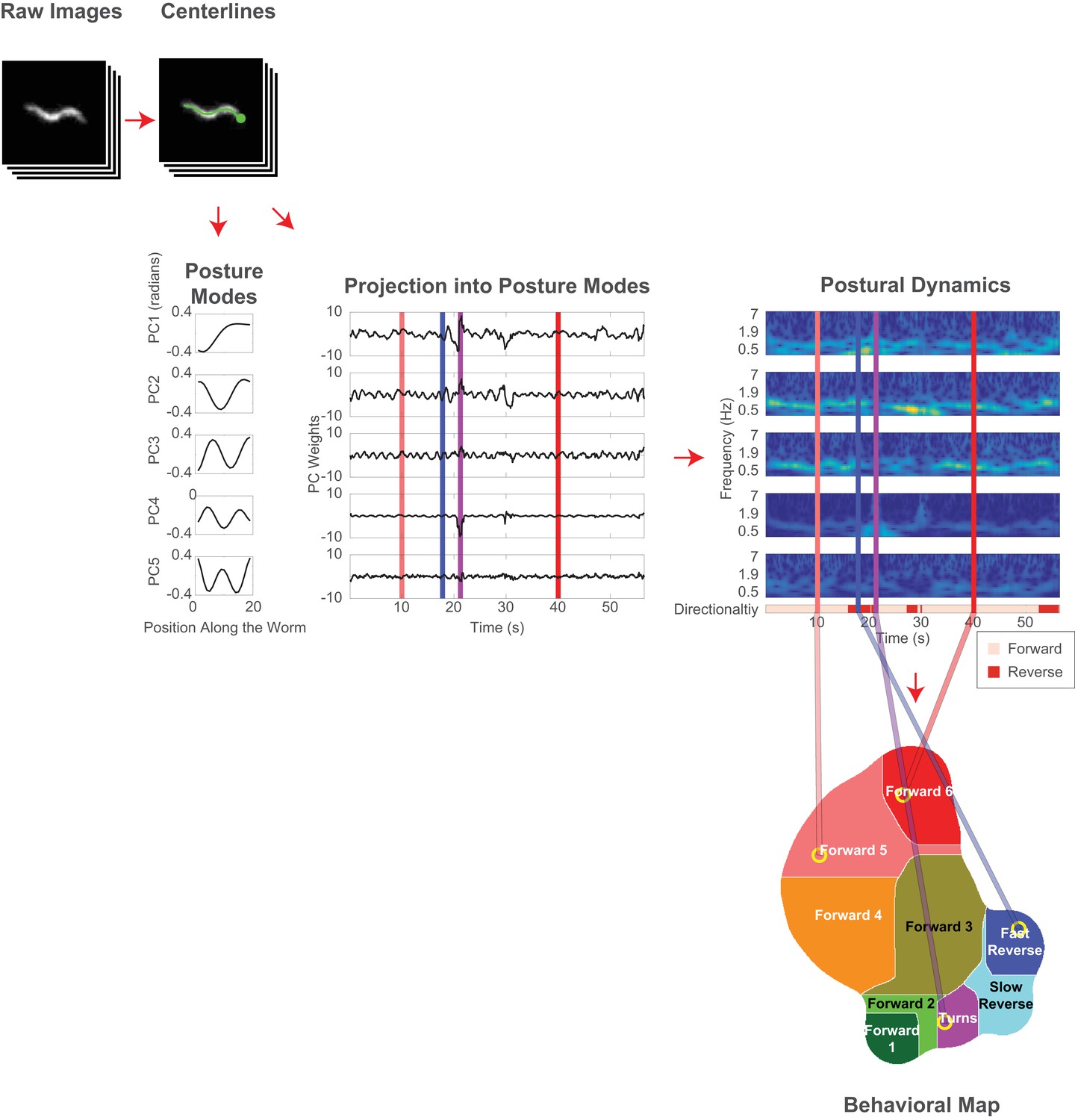

Armed with this massive amount of data, I applied unsupervised machine learning to cluster out all the different types of stereotyped locomotory behaviors, and then classify every animal’s behavior for every timepoint. After tracking the animals through time, I extract a centerline for each frame per animal. The dynamics of the centerline is analyzed by decomposing it via principle component analysis followed by a series of wavelet transforms in time. Each stereotyped behavior generates a unique 126 dimensional signiture in the wavelet space, which are projected down into a 2D map using t-stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE).

This clustering process produced 9 stereotyped behaviors. Forward1-6, Slow Reverse, Fast Reverse, and Turns. Forward1-6 are forward states with increasing velocity. Figure below shows example animals performing each of the 9 behaviors.

Following a single animal through time, we can see how the algorithm classifies the behavioral state of this animal.

Having developed a completely automated behavioral analysis pipeline, I was able to apply it to study how the animal processes touch information through time. Here is a summary of our findings written by the journal:

A worm called Caenorhabditis elegans has a nervous system made up of only 302 neurons, far fewer than the billions of cells that comprise our own brains. And yet these few hundred neurons are enough for these worms to detect and respond to their surroundings. C. elegans is thus a popular choice for studying how nervous systems process sensory information and use it to control behavior. Yet, most experiments to date have used only simple stimuli, such as taps or pokes, and studied a handful of behaviors, such as whether or not a worm stops moving or backs up. This limits the conclusions it has been possible to draw.

Liu et al. therefore set out to determine how the worm’s nervous system responds to more complex stimuli. These included physical stimuli, such as taps on the side of the dish containing the worms, as well as simulated stimuli. To generate the latter, Liu et al. used a technique called optogenetics to directly activate the neurons in the worm’s body that would normally detect information from the senses, by simply shining a light on the worms. Doing so gives the worm the sensation of a physical stimulus, even though none was present. Liu et al. then used mathematics to examine the relationships between the stimuli and the worms’ responses.

The results confirmed that worms usually respond to simple stimuli, such as taps on the side of their dish, by backing up. But they also revealed more advanced forms of stimulus processing. The worms responded differently to stimuli that increased over time versus decreased, for example. A worm’s response to a stimulus also varied depending on what the worm was doing at the time. Worms that were in the middle of turns, for instance, ignored stimuli to which they would normally respond. This suggests that an animal’s current behavior influences how its nervous system interprets sensory information.

The discovery of relatively sophisticated responses to sensory stimuli in C. elegans indicates that even simple nervous systems are capable of flexible sensory processing. This lays a foundation for understanding how neural circuits interpret sensory signals. Building on this work will ultimately help us understand how more complicated nervous systems interpret and respond to the world.